Paper, Ink and Passion: The Story of the Fanzine and Music ‘Zine Culture from Then to Here.

Part 1 of 3.

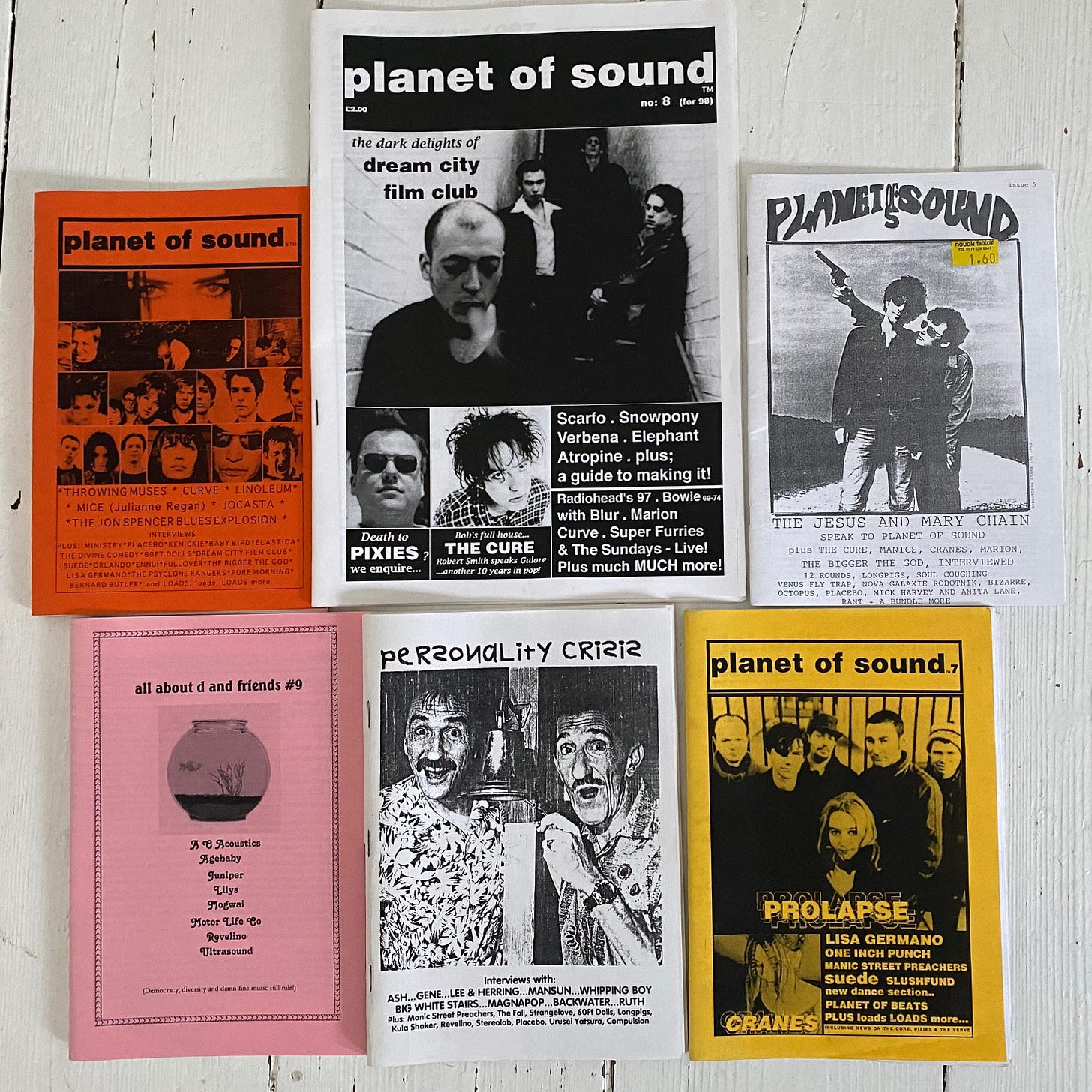

A flock of fanzine editors invited to BBC Sound City’s opening event in 1997, demonstrated the importance of music ‘zine’s. My invite to Sound City arrived by 1st Class mail in an envelope, with a cover letter and a pass tucked inside. Running my ‘zine Planet of Sound was my first taste of the music industry, writing about music, making discoveries. Between 1992 and 2003, Sound City was an annual music festival organised and broadcast by BBC Radio One - a precursor to the BBC 6 Music Festival launched in 2014. It gave alternative acts or left-field acts with mainstream potential, the much-required evening airtime in their natural environment on a live stage. The cross pollination between music fanzines and radio was obvious. The internet was just around the corner; but this was a time of paper faxes, email seldom used. Many people did not own a mobile, and those that did could only use their phone for texts and calls – I did not own one until later, in 1999 at the insistence of my bosses at Ignition Management. My landline at home had an answer machine that recorded to tape, accessible of course only by being physically present in my bedsit to press the play button. My fanzine was photocopied printed onto paper, each copy of each edition folded and stapled. The weekly music press was printed, at one time the NME sold 300,000 copies a week, Melody Maker 250,000 copies a week. Successful records sold in large amounts, in figures truly unfathomable today. Healthy times. Gathered in Oxford as guests of the BBC, we were on the eve of a shift that had already begun. This technological shift went far beyond music and the bands we’d be watching that evening after the press conference and early evening social events fuelled by free drinks. The world was soon to change immeasurably and so to our lives and those beyond.

Content on platforms owned by billionaires displayed on the screens of expensive handheld hardware made in factories by child labour would soon replace all that had come before. How would that have sounded to people in 1997?

Music fanzine culture most notably arrived and thrived in the UK from the 1970’s, from the birth of punk, far into the late 1990’s. Each generation of music fan having its cherished reference points. Music fanzines are now commonly misconstrued as content put to together in worship of a specific pop deity. Elvis or Madonna. Or perhaps more likely; Crass or Bikini Kill. Most commonly however fanzines seldom focused on one artist. ‘Fanzine’ was a term that stuck for anybody or any group of people producing a do-it-yourself publication, covering a variety of artists and bands, nightlife, gigs, club culture, protest, politics, capturing an emerging zeitgeist, a genre with multiple acts, or all the above over fifty pages. Largely written by passionate aspiring young writers in minimum wage jobs or unemployed. Most of all, fanzine’s were a vital connection between underground acts, movements, and their audience. Fanzine’s and notably their editors, were culture messengers and connectors in many senses. The written word circulated in print. Said artists, movements and influences going overground into broader mainstream culture was often possible. The surrealists, Dadaism, Bauhaus, the beat poets – all had some similarity to the essence of fanzine culture. Motivated on one level by mediocracy, and a feeling of not being confined to what is offered by the mainstream. Go create. Be progressive. Subvert. On another level encouraged and inspired by great music, its attitude, and the vibrancy of new discovery. Punk, acid house, and the multiple DIY scenes of the 90s all had vital connections to fanzines – fanzines as calling cards to new audiences and communication to existing communities. Fanzines were a phenomenon that arose for expression for those without a voice, to find a voice by do-it-yourself perseverance, pure independent publishing at every step, fuelling a ripple effect of progressive change across media and culture, forging vital connections and sowing seeds of opportunity.

*

In the digital environment of today, paper and ink fanzines have seen a resurgence in recent years. Each generation of music fan had previously had its fanzines; giving people voices, telling stories, making connections; fanzines had thrived for decades, but came close to dying out altogether. The voice of youth culture, counterculture, and rebellious upstarts, went digital, in similar spirit, e-zine’s emerged – but largely people flocked to social media to chat or more often shout at each other, or post links to You Tube videos. A physical fanzine drought had ensued. Gone forever some assumed.

Twenty five years later a resurgence of fanzine culture has been acknowledged in a broader sense than ever before. Offline media has seen a small but mighty resurgence. It will be interesting to see if this trend develops. Will there be a substantial return to physical DIY fuelled works, following a comparable decade long resurgence of vinyl records? Records sound better than MP3’s. Will a new wave of DIY publication read better than what is already online, offering depth, new voices, and perspectives? A physical manifestation of a reaction to the digital algorithmically forced soundbite, clickbait, disinformation, a reaction against an age of lacking substance, expert bashing, and the death of healthy discourse beyond the podcast?

Continued. My fanzine story, fanzine culture, other notable fanzines and the people that ran them (incl the likes of Alan McGee, Mark Perry, James Brown, Terry Farley, Everett True…)