Paper, Ink and Passion. The Story of the Fanzine and Music ‘Zine Culture from Then to Here.

Part 2 of 3.

Part 2.

Creating my own DIY music magazine, music fanzine, or music ‘zine, as they came to be known was a lifeline and connection to an orbit I previous had had no chance of entering. Although not fully conscious of it at the time, I was disconnected socially, economically, and geographically. My parents did not work in media, publishing, music, or anything like that. My background was based on the go-getting working-class traits that hard work earns a wage. Growing up in the isolated fields of the English countryside, far down a long track that connected to a tarmac road and some miles later, civilisation, did not help. While it was peaceful and the air was cleaner, there were no gigs, no clubs, no places to meet fellow youngsters out of school with dreams of escape. The radio was a key connection to music and culture beyond. I created my fanzine simply because I loved discovering new music.

Through sheer determination and my love for music I used paper, ink and passion to create Planet Of Sound in the mid 90’s. I began a journey that would lead me to places previously unimaginable, where dreams are made and fulfilled. This began with reviewing albums and singles, writing opinion pieces, and interviewing bands. Sometime later this would lead me to working for record labels; signing bands and making records in places such as Sound City, Los Angeles and Monnow Valley, Wales – moving to London, and establishing my first career.

Having flirted with fanzine creation in my teens, my first being Ascension, never distributed, I began Planet of Sound in the summer of 1995 which blossomed and carried on through to early 1998. Copies were sold in independent record stores such as Oven Ready Records in Aylesbury, Rough Trade shops in London and at gigs. Having graduated, unemployed and living back in my childhood home, I began to write. This became a music fanzine that would give me the ability to feel acknowledged, demonstrating I had a voice informed through an overwhelming appetite for music discovery. Multiple editions were created with some frequency. Opportunities opened. Connections were made. I discovered that this passion earned free records from music PR’s, new releases sent as promo CDs weeks before release, gig tickets, guest list places and most rewarding of all, meeting and interviewing bands and artists. The creation of my fanzine gave me freedom. I could have a good rant without editorial control. I could decide which band featured as the lead photo on the front page. I would later choose contributing writers to enhance the publication’s voices, reach and coverage. The freedom allowed me to grow my prior lacking confidence; as a writer, an editor and most importantly as an emerging young adult - before the constraints of larger adult responsibilities became regular visitors for my time, energy, and attention.

Music fanzine culture in the UK had spawned most notably from the punk era of 1976 onward, it grew in the 80’s and thrived in the 90’s. Many future music journalists, writers, publishers, editors, and creatives started their careers in their bedroom writing about bands with youthful enthusiasm. Before the internet, fanzine culture thrived, in every city, broadly, music-heads, writers and artists, often producing output reflecting new sounds way ahead of its coverage in mainstream publishing, these pioneers, those ahead of the curve, founders, the hustlers, those creators of music culture’s progressive axis.

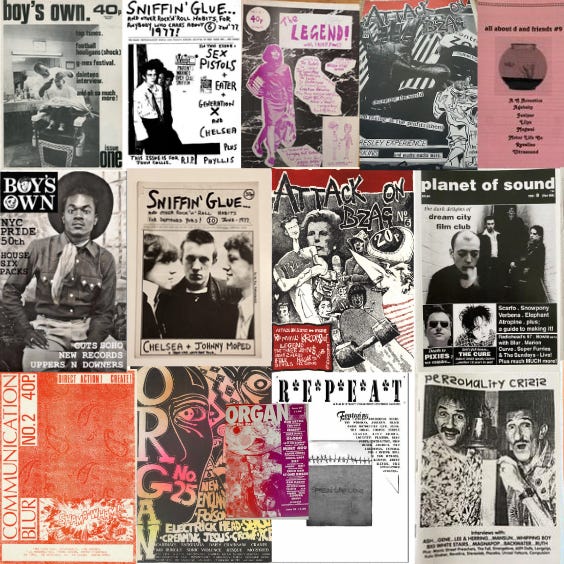

The DIY underground press and ‘zine culture was a bedrock of talent where new writers, artists, labels, rebels, and entrepreneurs emerged. Music fanzine’s had been a global phenomenon since the mid 60’s, a growing movement of DIY publishing in the face of mainstream mediocracy, a mainstream afraid to take chances and cover subcultures, protest movements, and alternative music scenes. DIY publishing grew as a result in the 1970s and preceded as a healthy counter point to the mainstream for the next three decades. Paul Williams Crawdaddy! and Greg Shaw’s Mojo Navigator grew out of San Francisco. The most notable fanzines in the UK begin with Mark Perry’s Sniffin’ Glue from 1976 covering the punk scene from London, and onto Terry Farley’s Boy’s Own fanzine in the emerging acid house era, 80’s indie ‘zines Everett True’s The Legend! – who later worked for Melody Maker, media publisher James Brown’s Attack On Bzag, and Creation Records founder Alan McGee’s own fanzine creation Communication Blur. Onto the 90’s and the birth of Planet of Sound, Anna Derbyshire’s Personality Crisis, Dee Barnfield’s All About D, Richard Rose’s R*e*p*e*a*t and Sean Worrall’s Organ fanzine, just some of many notable - hundreds more in existence. Hundreds of enthused music lovers writing about music and culture that defined the time. Discovering great music, some bad music too. There were also club football fanzines, sometimes overspilling into music and fashion, Paul Hooton’s The End a key example, Hooton later fronted the band The Farm. The fanzine scene was buoyant and vibrant, connected to the underground, one step ahead on new music, often breaking artists, bands, and stories, building platforms for bands and movements often before recognition from the NME and Melody Maker, and certainly ahead of broader mainstream media. Many fanzine writers went on to write for said weekly ‘inkies’. I was headed that way, I’d visited King’s Reach Tower, home of the NME and Melody Maker, but took a detour opportunity to get closer to the music, working with artists at record labels.

Fanzine culture was thriving, across the UK and beyond, but challenges were soon to arrive.