Paper, Ink and Passion. The Story of the Fanzine and Music ‘Zine Culture from Then to Here.

Part 3 of 3

Part 3.

Things were changing fast. Digital interaction replacing paper pages.

The internet arrived and began to dominate our lives. Creative enterprise at any level faced a fight for its very survival. While the internet offered opportunity, it offered a great deal of existential challenges - with rapid change on a continuous loop that would never ever seem to slow down. Many creative people’s livelihoods began to suffer greatly. Ultimately, we arrived at an age when a creative work online would commonly not earn the creator a penny for their efforts - or potentially get lost in a sea of hate fuelled rants and cat videos. Copyright and intellectual property rights were voided in the emerging digital economy (see; 1998 DMCA legislation effects), in favour of a new generation of digital enterprise geared for ad revenue capture, profit and stock market listings. The resulting effects were global. From the turn of the millennium, print publishing began to suffer, the fanzine scene wobbled too.

Everything was now conceived as free. Countless long nights typing offered little reward and opportunity for those looking for a livelihood doing what they enjoyed. Mass redundancies at record labels and media publishers ensued at both major and independent levels. Underground media developed online, of course, driven notably by the emerging concept of chat rooms - a precursor to social media. The new millennium brought in a wave of digital publication, ‘webzines’ and blogs. No one had to leave their bedroom anymore. Personally, I’d previously taken eighteen years to try and leave mine. I was not going back. In the new culture of free, webzine’s arose written by people who could still benefit from living with their parents. I myself, had moved on, now making records. This opportunity and the transition would have been unlikely without my fanzine and the connection and visibility it created. Some of the most dedicated and talented digital ‘zine creators of this era would forge similar paths into publishing and the now choppier waters of the music industry.

As digital consumption rose, physical publication became more niche than ever. Then came the collapse of the music paper heavy weights, the publishing conglomerate owned NME faded, the Melody Maker scrapped, once key lifelines to music discovery for many. Social media and You Tube were the new winners for music exposure. Bite sized consumption. Advertising dollars. More cat videos. More advertising revenue. ‘Get with the new age’ – but it lacked something, I for one missed depth and substance. Interviews and features that lasted more than a paragraph with a large photo. Updates of tour announcements were lost on a busy never-ending newsfeed. I wanted to pause, gain substance and turn pages.

But this was not the end of print, and notably fanzines.

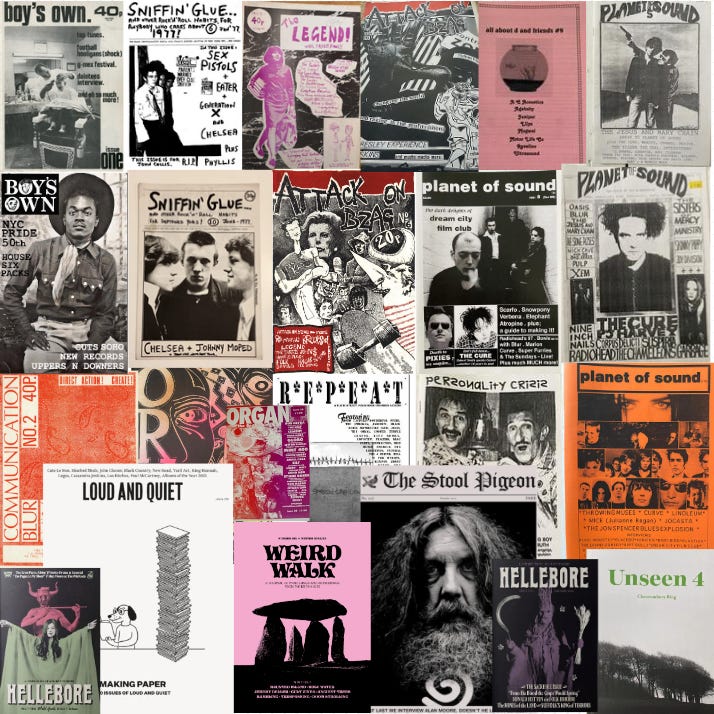

Paper and ink began its gradual return with the likes of Stephen Ackroyd & Emma Swann’s This Is Fake DIY, and later Stuart Stubb’s Loud and Quiet and Phil Hebblethwaite and Mickey Gibbons’s Stool Pigeon both launched in 2005. These developed into independent publishing ventures. Very welcome for readers wanting depth and discovery, at a time the frail remanence of the more traditional music press weeklies (NME now online under new ownership) seemed more geared for clickbait pictures with a news story paragraph about so-and-so pop star having a butt lift. Physical copies of new titles for a new age emerged and found a presence again with stockists. Analogue only DIY rebirthed. People wanted to read beyond the headline. People also wanted a break from the screen. This physical re-emergence of the fanzine was not just dedicated to music culture. In more recent years fanzines on ancient stone circles, pagan folk horror, protest, tattooing, photography, environmental issues, walking trails, and nature, all exist in a contemporary sense. This time printed survival is tougher in a world of digital distraction, but fanzine culture has returned in an even broader topical form than ever before. The fanzine culture ecosystem is vibrant. Will it be sustainable?

The original fanzine ecosystem always formed part of the overall music and media industries, leading to the cross-pollination of ideas and influence; but in a purely independent way, funded by various means, whatever it took; an occasional advert, mostly the cover price. Printing fanzine copies, even by photocopying methods, was an expensive pursuit, especially for people living on a diet of cheap pasta, such as I. Critically, in the mid 90s the healthy fanzine scene was recognised as a path for emerging talents, both for the writers and the bands championed. For some fanzine editors, such as myself, great opportunities were found, some at record labels. A handful of fanzine editors launched their own record labels if they were lucky to have the means to do so.

Well over two decades on from my invite to BBC Sound City, as a result of running Planet Of Sound, what use is a fanzine now? In the context of a world questioning the merits and threats of artificial intelligence - which can write and source anything you ask it to – where does the purely physical creative media medium of the fanzine fit in? Well, there will always be an audience for in depth substance and passionate writing about discovery, on a variety of topics, relatable in their connection. The inquisitive will continue to explore. The multi-thousand-year trait of human story telling will be threatened, but never equalled or surpassed – at least I hope. For music specifically, there is still lots of great new music emerging - written by humans, not machines -that will always be energised by those buzzing on music discovery and a desire to tell others. Music for the soul. The manifesting of subcultures. Of the fanzine format itself, could this be a remaining form of both protest and mass communication? Passed by hand. Off grid. Away from the reach of technological control, the threat of digital deletion and cancellation, away from the unmoderated algorithmic influence owned by a billionaire elite. As political and environmental activism enhances, with a soundtrack and a determined sense for positive action. For simply just reading a passion topic in peace, away from digital distractions. Whichever agenda or purpose. DIY publishing is still very much active. Paper and ink still have a place, after all. For whatever cause, it seems more than ever, recent times have shown us once more, that the pen is mightier than the sword.